There are so many from the past who’ve helped shape our hotels and community into what they are today. And during Black History month, we’d like to spotlight a few of them. From a friendly face who greeted guests at the mineral spring, to a world-famous boxer who trained here, to the baseball diamond and Black heritage church in the community, we remember some of these stories from those who left an important legacy.

Yarmoth Wigginton

You could say he was an influencer of his day. A person everyone recognized and knew; someone who even helped shift views and opinions.

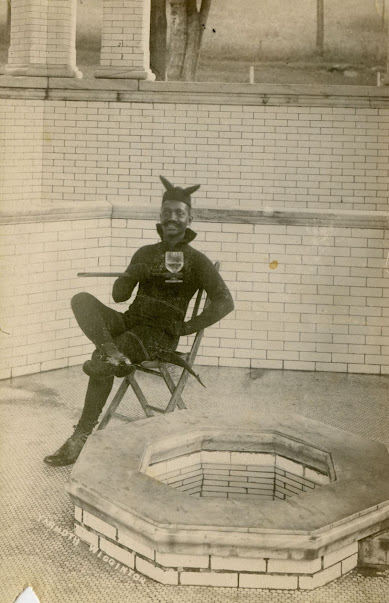

Yarmoth Wigginton was his proper name. But to local residents and visitors of French Lick Springs Hotel, he was better known simply as “Pluto.” Yarmoth was the water server at French Lick Springs Hotel, dipping probably thousands upon thousands of servings of mineral water for guests frequenting the springs. In numerous historic photos from the late 1800s and early 1900s, he’s dressed as the “devilish” Pluto Water mascot.

Born in Bloomfield, Kentucky in 1870, Yarmoth came to French Lick around age 18. He was likely among the first Black workers at French Lick Springs Hotel during this post-Civil War era when African Americans began moving north to look for work in Indiana and other northern states. From his beaming smile in the old photos at the Pluto spring, and some of the written accounts of Yarmoth, you get a picture of how he made a major impression on those he met – and earned respect during a time when gaining acceptance wasn’t easy.

When he wasn’t charming guests at the hotel, Yarmoth was involved in other civic organizations in the area. He was a member of the Knights of Pythias (whose headquarters were in the second floor of the building that now houses the French Lick West Baden Museum) and the Masonic Lodge. He also authored a column for the local newspaper that highlighted what Black people in the community were contributing and accomplishing – with hopes it would create a better understanding of people of color, thus benefitting both races.

After Yarmoth died in 1923, an account of Yarmoth in the local newspaper recalled that “he was a man of genial and happy disposition and no one could hold a grouch very long if brought under his radiant play of wit and humor.” And there were plenty more kind words in the newspaper pages to put the legacy of this trailblazing employee and citizen into perspective:

“The Valley has indeed lost one of its most valuable assets in the person of Yarmouth (sic) Wigginton, known throughout the community as ‘Pluto.’ … He came to French Lick in 1888 and here he had toiled and made a reputation to be envied by the highest as well as the lowly. In every avenue of life where true manhood and courage of conviction was required, he was there, to play his part for the advancement of his race and the community. He realized to the fullest that no part of a community can be regraded or kept down without lowering the remaining part. Thus he worked not only for uplift, but interracial understanding. Such a citizen, though humble, may not walk Legislative halls, nor boast of College Degrees, leans a silent influence that makes the coming generation, better citizens, place to his ashes, and comfort to his family. Twas truly the passing of a great man whom the community will find it hard to replace.”

Joe Louis

The “back” entrance to West Baden Springs Hotel on Sinclair Street takes you along a brick road and over a bridge standing over a creek. Pretty standard stuff. Until you realize that 80 years ago, you might have spotted the world’s best boxer here, running the streets on a training workout or casually fishing off the bridge.

This Joe Louis Bridge is named to honor the famed “Brown Bomber” who was the world heavyweight champion from 1937 to 1949 and used West Baden as his training grounds from early 1935 through late 1950. Legend holds that Louis could often be seen running through the steep streets in town, with little kids sometimes trying to run alongside and feverishly trying to keep up with one of boxing’s all-time greats.

During this era of segregation, Louis stayed at the Waddy Hotel, a hotel for Black guests on the east side of the bridge. And can you imagine how much it takes to feed an elite boxer in training? A published account from a chef at a West Baden hotel (likely the Waddy) reported that Louis liked pork chops and eggs for breakfast, and the champ was capable of consuming an entire pie for dessert.

Today you can take a stroll down Joe Louis Bridge with a plaque remembering one of the community’s adopted sons. It reads in part: He loved West Baden Springs, and he was loved by its residents.

The Waddy Hotel

A little more about the Waddy:

The two-story boarding house was built around 1910 and was one of two hotels in the community that accommodated Black visitors. Rice’s Hotel was the other, but the Waddy the more prominent of the two and hosted some famous guests.

Anita Patti Brown, a famous concert singer of the era, stayed at the Waddy and performed at West Baden Springs Hotel in January 1917, just days before the hotel’s opera house was destroyed in a fire. Brown, known as the “globe-trotting prima donna,” was considered to be the first Black concert singer to have her voice recorded. Also in 1917, Margaret Washington, the widow of Booker T. Washington, stayed at the Waddy during a visit to speak at a school graduation.

Artie “Smitty” Smith, a member of Joe Louis’ entourage, bought the Waddy in 1942 and expanded it to host ballplayers, boxers and other famous guests. After a fire destroyed the hotel in 1951, Smitty and his wife built a home on the site, where he lived until 1996.

The First Baptist Church

French Lick and West Baden Springs Hotel aren’t the only incredible stories of rebirth in this community. A group of volunteers rallied the restoration of a 102-year-old church in West Baden Springs, and they’re “re-ringing the bell” of the last Black heritage structure that still remains in this area.

The sign by the steps leading up to the church — it reads First Baptist Church (Colored), Est. 1909 — tells of a church whose history took shape in a very different era.

When Black workers came to this area to be cooks, waiters, porters, maids and bellmen, West Baden Springs Hotel owner Lee Sinclair realized how important it was for them to have a place of worship to call their own during this segregation era. Sinclair donated the land for the church to be built on, and it first opened for worship in 1920.In the coming decades, when West Baden Springs Hotel closed and the area’s Black population dwindled, the church closed its doors as well. But recently, a group of volunteers from Bloomington took on this passion project of giving the hotel a facelift and bringing it back to life. They held a re-dedication service and sermon a little over a year ago, and today the church holds a worship service for all visitors every Sunday.

The West Baden Sprudels Baseball Team

Wild as it sounds, our little community was once synonymous with some big-time baseball talent.

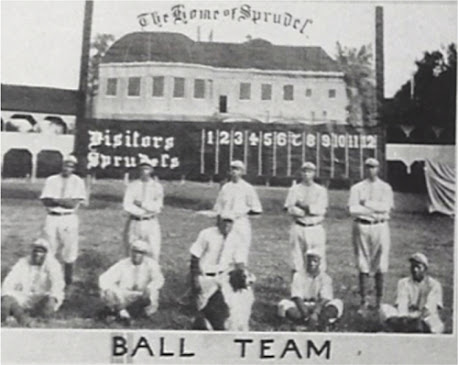

It started around the turn of the 20th century, when French Lick and West Baden followed the practice of many resorts that sponsored amateur baseball teams in the wake of the Civil War when baseball was gaining popularity in America. In those early years, West Baden’s team – known as the Sprudels – was comprised of several Black players who were employees of the hotel. During their non-working hours, the Sprudels would entertain guests in exhibition games played on the hotel grounds.

The Sprudels baseball team, circa 1910. The members are not identified, but Charles Taylor, the coach of the team, appears to be in the middle of the front row with his brother Ben (a future Baseball Hall of Fame inductee) to his right.

Then in 1910, Charles I. Taylor amped up the baseball scene even further. A legendary player, coach and later the co-founder of baseball’s Negro National League, Taylor relocated his Birmingham Giants to West Baden Springs Hotel and took on the Sprudels name. The Sprudels held their own (and even sometimes won) against major league teams who visited West Baden for spring training. And they produced legitimate stars like Charles' brother, Ben Taylor, who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006 after a successful stint in the Negro Leagues as a player and coach.